After the buzzer sounded and her shot fell through the net, Morgan William was mobbed by her Mississippi State teammates. All the opposing coach could do was smile as he watched the celebration in defeat. A two seed defeating a one seed in the semifinals of a college basketball tournament is not an uncommon feat, so why was this particularly stunning? It’s because this particular upset ended what is probably the most dominant stretch in the history of American sports. The team Mississippi State beat to move on to the NCAA finals was UConn – a team that had won 111 consecutive games. That streak was 21 games longer than the second-longest win streak, which also belonged to UConn. A week later (April 2, 2017), when Mississippi State hoisted the championship trophy, they became the first school not named UConn to do so in five years.

Speaking of 2017 — In 2017 the Clevland Indians, only ten months removed from garnering the unfortunate distinction of being the team that ended the longest futility streak in American sports history (the 108 years the Chicago Cubs went without winning a World Series), won 22 consecutive games, an AL record.

Baseball, being a game of history and an ingrained part of America’s shared heritage, glorifies streaks more than any other sport. Fans wax nostalgic about when Cal Ripken Jr. broke Lou Gerhig’s streak of consecutive games played (2130) in 1995. Ripken went on to play in 2632 consecutive games.

As impressive as Ripkin’s streak is, one can hardly discuss famous baseball streaks without mentioning the game’s single most revered streak: Joe Dimaggio’s 56 consecutive games with a hit. No player before or since has come within ten games of this record, and only two players in the last 100 years have come within 15 games – Pete Rose (44 games in 1978) and George Sisler (41 games in 1922).

So why do we love streaks so much?

Probably because we all love greatness, and the only thing greater than greatness is sustained greatness. None of these streaks were achieved by just being great, just being lucky, or just showing up every day. It is a combination of the three. All of these streaks required years of hard work that the spectator will never see; they required an unflagging determination to be the best – every day- when most of us get too mentally fatigued to wash our hands regularly during a pandemic; and they required the wings of a distant butterfly to flap at beneficial intervals.

Every time one fails to extend a streak, the counter resets to zero. All it takes is one bad bounce, blown call, or injury, and you are suddenly Sisyphus at the bottom of the hill. Unlike Sisyphus, we are mortal, and our athletic primes are minuscule segments along the line that is eternity. So when Sisyphus will restart his ascent, we can only look at the mountain and then the boulder, and hang our heads.

Just before Memorial Day, a member of my running club for Phish fans challenged the group to a Memorial Day to Independence Day run streak. The only rule was that you had to run at least one mile every day for the 40 days between Memorial Day and the 4th of July. Easy peasy lemon squeezy. I did not hesitate to accept this challenge.

Stage One: Denial

It was about a week into the challenge when I had a conversation with one of my myriad accountability partners in which I suggested that I might try to blow the doors off the 40-day challenge and shoot for 56 days as an homage to Joe Dimaggio.

To celebrate my first 7-day run streak since high school, I ran a 5-kilometer run at race pace. This was arrogance. I only had to run one mile to extend the streak. I was going for triples when all I needed was a base hit.

Stage Two: Anger

On day 12, I ran a D-Day 10k. My time was only ten seconds faster than my previous 10k, nearly one month earlier. I was running more, but I was not giving my body time to recover, so my times were suffering. When I expressed disappointment in my lack of progress, a friend helped me put it in perspective by reminding me that it was, “Better than ten seconds slower.”

On top of general fatigue, I was developing shin splints, so my mile “preservation” runs were roughly one minute slower than my typical mile. Needless to say, I was frustrated, and only two weeks into the challenge, I started thinking that I would not make it to 40 days, let alone 56.

Stage Three: Depression

I was fatigued, I was in pain, and I wasn’t going to get better until the challenge was over. It was 25 days into the challenge that I realized that my mile-long preservation runs were not long enough to be considered a full cardio workout, so, in a sense, what I was doing was counterproductive to my fitness goals.

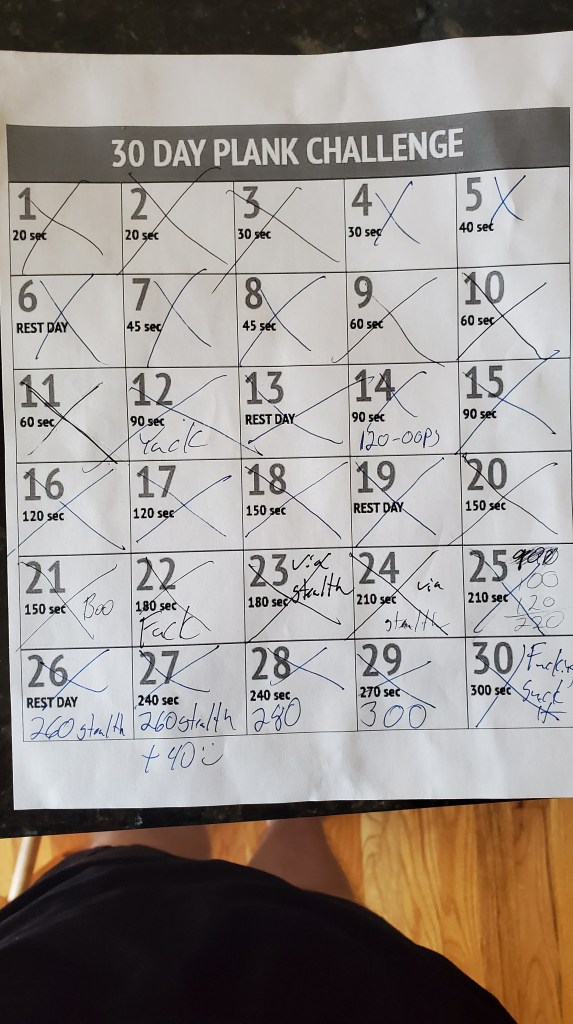

I had already added a plank regimen to my routine (30 Day Plank Challenge), but even that wasn’t enough.

Stage Four: Bargaining

Me: Alright, Tom. Time to run.

Also Me: I don’t wanna.

Me: If you run just one mile, we will go to Starbucks for a nitro cold brew.

Also Me: With honey and sea salt?

Me: Let’s see how our run goes, and if I feel like we earned honey and sea salt, we can get it, but if we are dogging it out there, we’ll only get the cold brew.

I had to make this deal four times during the 40-day challenge.

Stage Four and a Half: Wait…did I do the math wrong?!

This was a 40-day challenge, but after my run on day 37, I realized that I still had four days left until the 4th. A quick Google search confirmed that it was 40 days from May 25 until July 4, but how could that be? After counting each square on my calendar, my suspicions were confirmed — it was a 41-day challenge.

Stage Five: Acceptance

Exhausted, sore, sunburned, and under-motivated, I resigned to coast through the last week of the challenge by only running one mile per day, and my stretch goal of 56 days was out of the question. If I hurt myself and had to rest for an extended period of time, this whole thing would have been a detriment to my fitness. This might be considered “playing not to lose” rather than “playing to win,” but it was the smart thing to do.

Sometimes I would have to run before work; other times, I would run well after the sun went down. Sometimes I was wearing a poncho; other times, I was wearing short shorts, also known as “ranger panties” (mostly after the sun went down). Most of the time, I was sober, but one time I wasn’t (that wasn’t very smart, and I will be the first to admit it).

At the end of 41 consecutive days, I had logged 88 miles without any real injuries, which is a win in my book. I would not have participated in this challenge had it not been for my friends, and if I had, I probably wouldn’t have finished without them spurring me on. Tomorrow my boulder will roll to the bottom of the hill, and I do not intend to chase it.